Murphy can play the fashion queen with as much hauteur as any of them – glamour and nightlife have always been serious business for her – but her full-bodied vocal style recalls that of 1980s Dusty Springfield, with its mix of tenaciousness and vulnerability. Dua Lipa might do vintage disco, but it’s without the heartache or the wear and tear: her sound is sleek and markless, even by the standards of a 25-year-old. The production of Jessie Ware’s most recent album has a glossy, ageless veneer, considerably slicker than that of her extraordinarily sensitive 2012 debut, “Running”. Vincent are airbrushed out of sight: they are glacial sci-fi goddesses, impregnable to touch. Sonically and visually, Alison Goldfrapp and St. Kylie Minogue may be in her fifties, but her music certainly doesn’t push the age angle – her image is sealed as a perennial Aphrodite, golden and smiling. The days of Donna Summer and Barbra Streisand – who came together to sing of midlife anguish and everyday stresses in “No More Tears (Enough is Enough)” in 1979 – seem very distant. And, although the adult disco sound has been taken up by a number of contemporary female singers, very few acknowledge the effects of time or even of mortality in their mood and lyrics. The industry shrinks from age, perceiving it as the ultimate shabbiness – not only unmarketable but unfathomable, and lacking influencer cred. It is rare to hear an aged female voice in pop today. The Róisín machine is still driven by restlessness. The vocal has a hunger and urgency not often associated with maturity: a sense of compressed passion and ambition, a need to soar (“Maybe this could be the last time I feel the strain … life just keeps me wanting”). When, in the single “Something More”, Murphy sings of “young lovers in my bed” and “boys who ease the pain”, it seems like more than an affectation. It is an aged voice, capable of delivering a sense of yearning and frailty as well as toughness. This is not just the decorative rasp of a Lana Del Rey or Billie Eilish, signalling premature sophistication. It may be the most alluring sound in pop today.

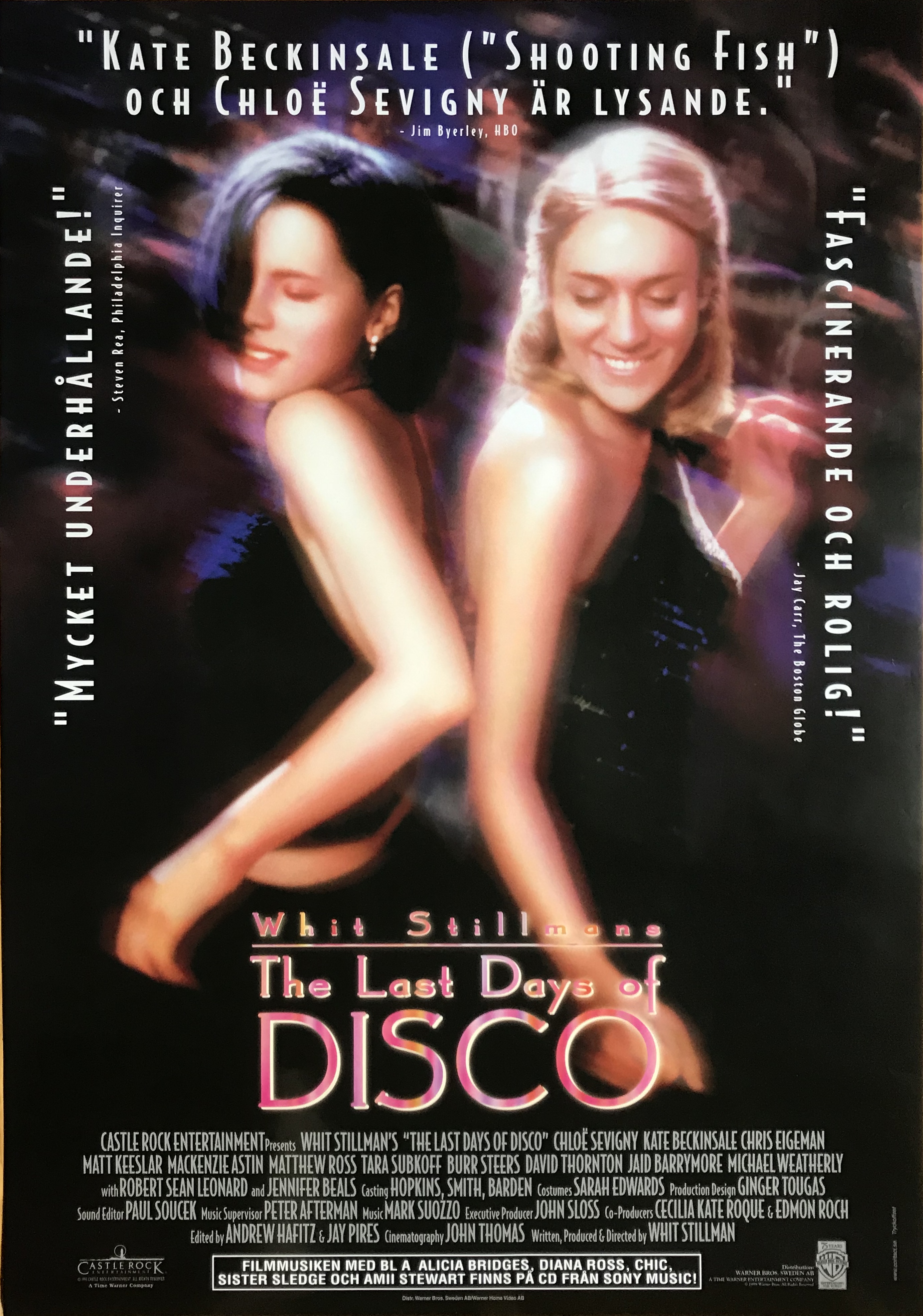

It is less supple than before, but has magnificent, wine-dark tones in its lower range, and the timbre is like a thick silk velvet, worn away in parts. On “Murphy’s Law”, that sprite-like quality has given way to a voice with distinct fibres and a built-in resistance to the groove. In “Sing It Back”, her tone was so seductively light she seemed to be embodying the siren sound of melody itself. She is no longer the darting, flyaway presence she was on her former electronic duo Moloko’s great club hits, “Sing It Back” (1998) and “The Time Is Now” (2000). At the age of 47, the Irish singer-producer has earned the right to a namesake track, as well as a self-titled album, nearly a decade in the making.Īn inveterate smoker, Murphy’s voice has thickened considerably over the years, and is all the more haunting for it. The unfurling of that voice reveals an artist at the height of sensual power. As the keyboard shifts into an irresistible groove, reminiscent of Donna Summer’s “Bad Girls”, the rich textures of Murphy’s voice become warm and softly coaxing. In the spoken intro, she comes across as a woman emerging from hiatus, trying out phrases against a sparse keyboard line. “Murphy’s Law”, the standout track from Róisín Murphy’s fifth solo album, Róisín Machine, is instantly beguiling. Róisín Murphy’s latest album is unusually mature pop driven by restlessness Stillman does interesting things with all of them. The characters include two young women in publishing (Chloe Sevigny and Kate Beckinsale) who find a flat together, their roommate (Tara Subkoff), an employee at the club where they hang out (the always interesting Chris Eigeman), a fledgling ad executive (Mackenzie Astin), a junior assistant district attorney (Matt Keeslar), and a lawyer (Robert Sean Leonard). Fortunately, this time around the Ivy League characters project less of a glib sense of entitlement, making them more fun to watch, and Stillman himself gives more evidence of watching rather than simply listening. It’s remarkable how over the course of just three nightlife features - Metropolitan, Barcelona, and this comedy set in the early 1980s - writer-director Whit Stillman has created a form of mannerist dialogue as recognizable as David Mamet’s, a kind of self-conscious, upper-crust Manhattan gab reeking of hairsplitting cultural distinctions.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)